By PATRICIA SANDERS

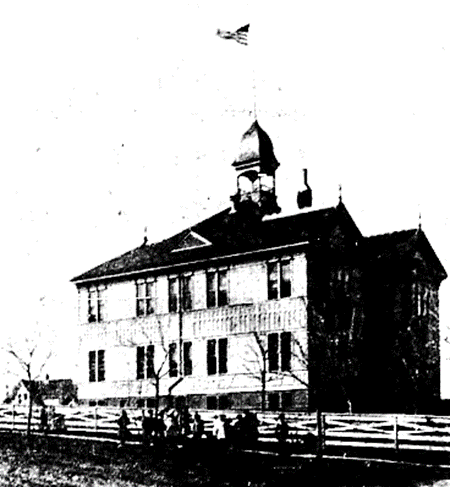

Montavilla Branch Library at E. 68 81st St. (now 422 SE 81st Ave.) in the 1920s.

Source: Multnomah County Library “The Gallery”

Today, if you live in Montavilla and want to check out a hard copy of a book or magazine, you must go to another neighborhood with a branch library. But from 1907 until 1981, you didn’t have to go beyond the neighborhood boundaries.

What follows is the complex story of how Montavilla went from having a small reading room in 1907 to a brand-new branch library building in 1935. It’s a story of dedication, persistence, and community effort.

The national free public library movement

You could say the story begins with the national movement to establish free public libraries in towns and cities across the land. Today we take such libraries for granted, but that wasn’t always so.

America’s earliest public libraries charged a fee. For example, Benjamin Franklin’s Philadelphia library, founded in 1731. This put them beyond the means of most Americans.

During the 1800s, the idea of free public libraries gradually caught on. The movement gathered momentum in the 1870s in connection with the public education movement in the United States. Public libraries were seen by their promoters as places where people could continue their education beyond public school. They were “the universities of the people.”

Women’s clubs were a driving force in the free library movement. We’ll see this was certainly true in Montavilla.

The story begins with Portland’s first free public library

Although Portland was a sizable and affluent city in the late 1800s, it had no free public library until 1901. But a library for subscribers was founded in 1864 by the Library Association of Portland. The fees were too steep for most Portlanders.

The Library Association of Portland established a subscription library in 1864.

Source: Forty-eighth Annual Report of the Library Association of Portland, Oregon, 1911

Another Portland library opened in 1891: the People’s Free Library (also known as the Portland Free Library). It was free in name only. Its fees were lower, but the collection was much smaller and still not affordable to all.

In the 1890s, numerous articles in the Oregonian showed a growing public desire for a truly free public library in Portland. Some called it “disgraceful” that a city of Portland’s population size and wealth lacked a truly free library. Many cities of the same size, or even smaller, already had them.

Not everyone agreed. Some said, what was not paid for was not appreciated. Free libraries could foster a spirit of dependence.

Proponents argued that the working classes and immigrants needed libraries. This was, after all, the Progressive Era, with its emphasis on improving society in various ways. Free libraries could help create the informed society needed for progress and democracy.

The Library Association hoped to reduce monthly dues, but they had “no intention of ever making it a free library,” they stated in the Oregonian of November 5, 1891.

In 1900, Portland merchant John Wilson (1826 – 1900) offered his enormous personal library of nearly 9,000 books on condition that they go into a free public library.

Portland merchant John Wilson’s generous bequest of books and money led to the establishment of the first free public library in Portland.

Source: Portland, Oregon: its History and Builders, vol. 1

Wilson’s bequest proved irresistible. There was a hitch, though: what would replace subscription fees needed to sustain the library in future years?

The answer came in 1901 when the Oregon Legislature passed a law allowing Oregon cities to collect a library tax from property owners.

In 1902, with financial support expected, the Library Association opened a free Portland library. Montavilla, of course, could not use this library since it was not yet part of Portland. That came in 1906 when Montavilla citizens voted for annexation.

The Multnomah County library system is born

In 1903, the Oregon legislature passed another law which allowed Oregon counties to collect library taxes. With this additional funding, the Portland library became available to all Multnomah County residents. The library tax law then went from optional to mandatory in 1905, making continued funding even more likely.

Now Montavilla citizens could use the downtown library. It was just a trolley-car ride away, but still not as convenient as a local library.

Aware of the need of county residents in outlying areas, the Library Association began to create “extension” services.

Beginning in 1903, the Library instituted regular delivery of books to suburban and rural communities. Boxes filled with books were dropped at designated “stations,” such as grocery stores and Grange halls.

Two book-boxes at an unidentified location. Statements on the poster express ideals of the public library movement: “Every occupation needs the worker who is well informed” (top) and “Knowledge is Power” (bottom).

Source: Multnomah County Library

By 1906, Montavilla had a book station: the dry goods store owned by Dan McMillan (1881 – 1966). This was in Montavilla’s commercial district, on the north side of Base Line Road (SE Stark Street) just west of NE 80th Avenue. Bessie McMillan (1880 – 1961), Dan’s wife, handled book circulation.

The Montavilla book-box station (and later the first Montavilla reading room) were in this dry goods store on Base Line between SE 79th and SE 80th Avenues shown here. This photo was taken after the fire of July 4, 1910. By this time, the Montavilla reading room was located on the south side of Base Line and was not affected by the fire.

Source: Oregon Historical Society

A book-box inside an unidentified deposit station.

Source: Multnomah County Library

Montavilla gets a reading room

In 1906, the county library expanded their outreach program to include reading rooms. The Library would provide books and a librarian, but the communities would have to fund the room rental plus heat and light.

Here’s where the community activists stepped in. The mothers and teachers of the Montavilla Home Training Circle began a fundraising campaign to raise funds to pay for a room, fuel, and lights— about $25 a month, they calculated. A reading room would be an educational asset and, so, it fit the mission of the National Home Training Association, which was established in Portland in 1904.

The HTC women had reason to anticipate success. In 1901, Montavilla raised enough money to buy 120 new books for the Montavilla School library, making this the best school library in the county, according to the Oregonian of January 3, 1902. The Montavilla School library was open to adult patrons as well as children, like other school libraries around the country. These could be considered precursors to local public libraries.

Montavilla School in 1907. This school’s library was the best in Multnomah County (outside Portland), according to the Oregonian in 1902.

Source: Beaver State Herald, February 8, 1907

As mothers and teachers, members of the HTC had a close connection to the Montavilla School. Lillie Bowland (1862 – 1944) is one example. She was the Montavilla HTC president in 1907 and 1908. She was a parent and teacher herself and the wife of Montavilla School principal, Nelson W. Bowland (1861 – 1950).

Lillie Bowland (1862 – 1944), president of the Montavilla Home Training Circle in 1907 and 1908.

Photo by permission of Britney VanCitters.

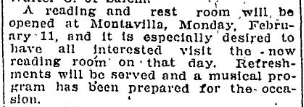

The Montavilla HTC fundraising campaign was a resounding success. The Montavilla reading room was one of only five reading rooms opened in 1907. It was set up temporarily in Dan McMillan’s recently-vacated store (site of the old book-box station) and opened on February 11, 1907. The hours were 3:00 p.m. – 5:30 p.m. and 7 p.m. – 9:30 p.m. Monday through Saturday. In its second month, it had 1,065 visitors.

The Montavilla reading room opens.

Source: Oregon Journal, February 7, 1907

Montavilla’s first librarian, Mrs. Theresa E. Mitchell (1854 – 1933), serving from 1907 to 1910, was the first of a succession of female librarians. Women librarians were the norm for the country because this was considered a female profession. Women were deemed temperamentally suited to it and were willing to work for lower wages than men.

The Montavilla reading room soon relocated. By February 1908, it was in Warren’s Hall. The hall no longer exists, but it then stood where the commercial building on SE Stark adjacent to the Academy Theater is today.

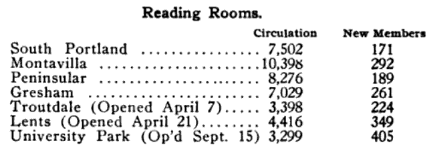

The Montavilla reading room proved popular, with a circulation of 10,398 books and 292 members in 1908. These are the highest numbers of all seven Multnomah County reading rooms.

Reading room circulation for 1908.

Source: Forty-fifth Annual Report of the Library Association

By 1911, circulation was up to 14,713, the second highest in the sub-branch category. With such a record, why not try for a Carnegie Library?

Montavilla seeks a Carnegie Library

In 1911, the Carnegie Library Commission offered Portland a $105,000 grant to create three new branch library buildings. Two were already designated for East Portland and Albina. Montavilla hoped to get the third one.

Book circulation was up and likely to increase since Montavilla’s population was growing. And a Montavilla library would also serve the neighboring communities of Mount Tabor and Russellville.

The Montavilla Carnegie library campaign began. A joint committee was formed by the Montavilla PTA (successor to the HTC) and the Montavilla Board of Trade. It offered a site and asked for $35,000 for a building. The Oregon Journal of May 23, 1911 said Montavilla had a good chance of getting a Carnegie library since it did not have a full-fledged library.

Despite the need and the endorsement of the Oregon State Congress of Mothers (precursor to the PTA), the campaign failed. The third Carnegie library went to North Portland.

Montavilla becomes a sub-branch library

In 1911, all the reading rooms in Portland were upgraded to sub-branch status. Local communities were no longer responsible for library costs. These would be covered by the Library Association.

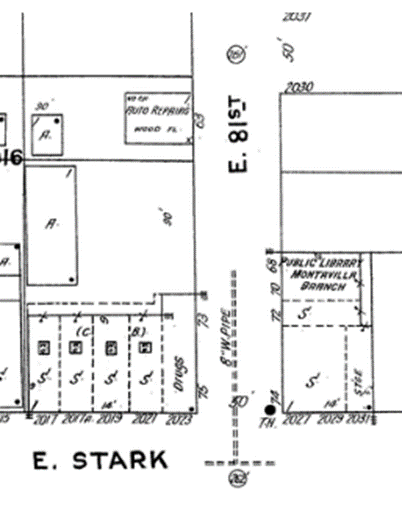

The Oregonian of November 17, 1911 announced that Montavilla would get a branch library building in 1912, but instead it moved into a single room in a new brick building at 68 E. 81st St. (now 422 SE 81st Ave.), the present location of the Miyamoto sushi restaurant).

The Montavilla sub-branch library was located at 68 E. 81st Street (422 81st Avenue) from 1911 until 1935, when the new Montavilla Branch Library finally opened.

Source: 1924 Sanborn Insurance map

In 1913, the sub-branch doubled its space by removing a partition and adding the store next door.

Daily life in the Montavilla sub-branch library: a first-person account of 1915

Newspaper articles and annual library reports, which are the sources of most of the information I found about the Montavilla library, give us mostly factual details. But a weekly column called “The Library,” published in the Montavilla Sun in 1915, paints a more detailed picture.

The columns were written by Ada S. Couillard, Montavilla’s librarian from 1914 to 1916.

The Library column by Ada S. Couillard, Montavilla librarian.

Source: The Montavilla Sun, May 7, 1915, page 1

Miss Couillard was a trained and experienced librarian before taking over the Montavilla sub-branch. She graduated from Wellesley College and worked at the Ohio State University library from about 1907 to 1909. By 1913, she was employed at the Oregon State Library. The following year, she became Montavilla’s sub-branch librarian. After leaving Portland, she worked at the University of Minnesota and finally at the New Jersey College for Women libraries.

With her distinguished background, did the Montavilla sub-branch seem like a come down? Her columns certainly show her awareness of the library’s shortcomings. At the time, it was one of the least patronized in the County. Couillard was dismayed that a community of 12,000 people had a monthly circulation of only 2,000 items. She questioned whether the community really needed a new building.

In her columns, she tried to build up circulation. She described the library’s holdings that should appeal to local interest in gardening, beekeeping, birds, travel, adventure, etc. She reminded parents of the Saturday children’s story hours. She pointed out the library’s subscription to 26 popular magazines. There were also books in Swedish for Montavilla’s significant Swedish population, and books in other languages could be requested from the main library.

Excerpt from Ada S. Couillard’s column demonstrating her efforts to increase the Montavilla sub-branch circulation.

Source: Montavilla Sun, March 12, 1915

Couillard was also frustrated by Montavilla’s apparent lack of interest in world and national problems. The library did have books on “the immigration question” and “the European war.” A person had no right, she wrote, to express an opinion on immigrants unless that person was informed.

Couillard used holidays and local events to attract readers. There was a May Day celebration with flowers decorating the library, for example. And as the Montavilla School graduation approached, she pointed out books that could help boys and girls decide about their next steps. Would they go on to high school then perhaps college? Or would they seek employment; she had books on vocations for both girls and boys.

A new branch library building, at last

In 1917, the Montavilla library was upgraded to a branch library and remained at 68 E. 80th Ave. until 1935. At that time, a purpose-built library designed by architect Herman Brookman (1891 – 1973) opened on the west side of SE 80th near the corner of SE Ash Street. The city of Portland donated the lots. The County Library covered the $7,500 cost.

Montavilla Branch Library opened in 1935. The building still exists, but with an added story.

Source: Multnomah County Library

The branch library’s 5,000 books were transported from the old store building to the new library with help from the Girls Scouts and Boy Scouts of Montavilla.

Left: Boy Scouts helping to move books to the new branch library.

Source: Oregon Journal, August 23, 1935. Right: Mrs. Phyllis A. Daugherty (1885 – 1970), Montavilla branch librarian since 1924, shelves books in the new library.

Source: Oregon Journal, September 1, 1935

Conclusion

As we’ve seen, it was a long road to a full public library in Montavilla. It went from books-by-the-box, to reading rooms, to a sub-branch, to— finally— a brand-new branch library.

The journey lasted almost 30 years and required neighborhood support all along the way.

This is just one example of the people-supported Montavilla neighborhood projects that gave us many of the other amenities we take for granted today: a public water supply, paved roads and sidewalks (in most places), and sewers, to name just a few.

The Montavilla branch library was in continuous service until 1981, when it became the latest victim of the severe financial problems that had plagued the Multnomah County Library system since the early 1970s. Budgets, services, and hours had already been cut first in the effort to keep the system alive.

For the Montavilla branch, the final blow came in June 1981, when a failed ballot measure led to the permanent closing of the Montavilla and the Lombard branches. Voters were no doubt swayed by the dire financial state of the American economy, which was mired in the worst recession since the Great Depression of the 1930s.

The doors of the Montavilla branch library closed in November 1981. The building was leased to the Oregon State University Extension Service until 2003, then lay vacant for two years. In 2005, Multnomah County Commission voted to sell the site, despite the proposal of Save Montavilla Library activists to re-open it as a volunteer-run library.

Fortunately, for all of Multnomah County, the library system has survived and evolved with the times.

Montavilla no longer has a branch library, it does have a growing inventory of little libraries with books free for the taking— thanks to our generous Montavilla neighbors.

The Montavilla community spirit lives on!

A little free library at 8024 NE Oregon Street, one of many in the Montavilla neighborhood. Photo by Samantha Stover

***

Sources:

The Oregonian

The Oregon Journal

The Beaver State Herald

The Montavilla Sun

Annual reports of the Library Association of Portland, Oregon

Cheryl Gunselman, “Library Association of Portland,” Oregon Encyclopedia

Chuck Spidell, Montavilla Free Libraries map

For more information on the 80th-Avenue branch library on SE 80th Avenue and some comments from its former users, see our previous story here.

***

If you have stories to share about the library, old photos of it or stories about other historic Montavilla people, places or events, please contact me at pat.montavilla.history@gmail.com.

Read all of the “Montavilla Memories” articles by Pat Sanders here.

Wonderful story about how dedicated people can make a difference!

LikeLike

Love this article showing how many dedicated people, over time, can enhance public opportunities.

LikeLike